It is exhausting to discover a science fiction fan who does not have a comfortable spot for steampunk. Usually understood as a subgenre targeted on the steam-powered equipment prevalent within the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth century and its hypothetical developments, the realm of steampunk is open to a number of variation and definitional debate. It contains works of exhausting, traditionally thorough sci-fi, in addition to pure fantasy the place the bells and whistles of early industrialization come into play as a freely-defined aesthetic. Something sci-fi with that vintage-advanced really feel, that emphasis on old-new rigidity expressed via dense industrial landscapes made out of brass and clock actions, can fall below this specific rusted umbrella.

Films themselves, these once-thought-impossible illusions born from Nineties machines, are probably the most steampunk of innovations — so it is solely acceptable that cinema ought to have a wealthy custom of movies that borrow from the style to construct out their worlds. Right here, we have now ranked the most effective steampunk films of all time, and you’ll find {that a} third of the record is made up of Jules Verne diversifications, a 3rd of it’s made up of animation, and a 3rd of it’s Czech. Put in your top-hat-and-goggles combo, and dive in.

12. Again to the Future Half III

In “Again to the Future Half III,” we choose up instantly after the “Half II” cliffhanger that left Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) stranded in 1955 but once more, whereas the 1985 model of Emmett “Doc” Brown (Christopher Lloyd) acquired zapped to the yr 1885. With assist from the 1955 Doc, Marty dusts off the DeLorean and travels into the previous, the place he and the 1985 Doc get caught up in a Western journey. After which there’s the kicker: As a result of the DeLorean’s gasoline line acquired broken in the course of the journey, they’re compelled to make do with late-Nineteenth-century know-how and nonetheless someway discover a approach again to their dwelling yr.

Might or not it’s the most effective “Again to the Future” film? Rather than the labyrinthine, flowchart-requiring temporal bustle of “Half II,” “Again to the Future Half III” gives a pared-down fish-out-of-water story about Marty and Doc fending for themselves within the Outdated West — a setup that opens up myriad golden alternatives for comedy and pathos. Each director Robert Zemeckis and screenwriter Bob Gale relish the chance to affectionately rib Western tropes, which make for a surprisingly apposite pairing with the franchise’s sci-fi slant. On prime of all that, “Again to the Future Half III” additionally turns into a sneakily nice steampunk movie in its again half, as Doc makes eye-popping technological miracles out of steam-powered machines.

11. April and the Extraordinary World

Few films incorporate the aesthetic of steampunk with as a lot dedication as “April and the Extraordinary World,” probably the greatest non-Hollywood animated films of the 2010s. Primarily based on the works of French comedian artist Jacques Tardi, the function debut of Christian Desmares and Frank Ekinci proposes an elaborate alt-history world through which Napoleon III was killed in an explosion brought on by a harmful scientific experiment, the Franco-Prussian warfare by no means occurred, and France has arrived to the yr 1941 below the rule of Emperor Napoleon V. On this alternate actuality, the world’s scientists routinely go lacking below mysterious circumstances. Consequently, know-how has remained caught within the steam age, and Paris is now a gritty metal metropolis with airship buses, crisscrossing ropeways, and two Eiffel Towers.

After establishing this stunningly attractive world of grays and reds, the film proceeds to play out a fancy, multi-layered sci-fi saga inside it. April Franklin (Marion Cotillard) is the daughter of two scientists who continued the life-extending experiments began all the best way again in Napoleoen III’s time and seemingly died for it throughout an escape from authorities brokers when April was a toddler. Years later, whereas persevering with her mother and father’ experiments, April discovers proof that they could nonetheless be alive — sending her on a search that tunnels into the darkish, perilous underbelly of this retrofuturist Paris simply as a lot as any steampunk fan may hope for.

10. Sherlock Holmes: A Sport of Shadows

Man Ritchie’s “Sherlock Holmes” movies are nice, truly. 2009’s “Sherlock Holmes,” for one, is a surprisingly enjoyable and spirited yarn. Its sequel, 2011’s “Sherlock Holmes: A Sport of Shadows,” is even higher. Working with an elevated price range and confronted with the expectation to go larger for the second spherical, Ritchie opts to have enjoyable with the very thought of a gun-toting, day-saving motion hero Holmes: The economic, implicitly violent panorama of late-Twentieth-century Europe will get decreased advert absurdum all the way down to a collection of organized cause-effect relations between machines and operators, till it capabilities as a chessboard the place strikes could be foreseen.

It is on this context that “A Sport of Shadows” casts Robert Downey Jr.’s Sherlock as each participant and commentator, prepared the motion blockbuster into being by deconstructing and reconstructing its method. Caught in a battle of wits with Professor James Moriarty (Jared Harris), who’s merrily transferring items into place for a world warfare that can profit him, Holmes embarks on a run-through of style tropes that he is capable of anticipate and shift round — thereby turning all motion right into a matter of mind. It is a thrilling homage-slash-subversion of style method, and Ritchie’s curiosity in steampunk markers is integral to it. Each explosion, each click on of each gun, and each different technological extravagance turns into one other shift of gears within the nice contraption that’s the world in Holmes and Moriarty’s eyes.

9. Hugo

Martin Scorsese has tried his hand at many various genres, however “Hugo,” his 2011 incursion into kid-friendly journey cinema, is one thing particular. Tailored by screenwriter John Logan from the illustrated novel “The Invention of Hugo Cabret” by Brian Selznick, Scorsese’s most awarded movie ever on the Oscars (tied with “The Aviator”) follows Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield), an orphan boy residing within the partitions of a prepare station in Nineteen Thirties Paris.

Hugo is decided to restore an automaton left behind by his clockmaker father (Jude Legislation), utilizing notes that his father put down in a pocket book. Someday, he’s caught stealing components by surly toy retailer proprietor Georges (Ben Kingsley), and when George takes away Hugo’s pocket book as punishment, he agrees to work on the retailer as compensation. Quickly, Hugo strikes a friendship with Georges’ goddaughter Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz) and learns that Georges is the truth is legendary 1900s filmmaker Georges Méliès, thus opening up a larger thriller that will join the store, the automaton, and the early days of cinema.

Scorsese shoots all of this intrigue as a rambunctious blockbuster, full with James Cameron’s favourite use of 3D in a film, and the retro-sci-fi parts of Hugo’s investigation are all steampunk to the hilt. The entire film looks like a diorama in one of the best ways, as if you could possibly attain out and contact the prepare station’s intricate metallic constructions along with your fingers.

8. Invention for Destruction

Czech filmmaker Karel Zeman was a pioneer of lavish, artisanal particular results who catapulted sci-fi cinema a few half-century ahead along with his bold midcentury productions mixing live-action and animation methods. Two of the movies on this record are his, together with this one: 1958’s “Invention for Destruction,” probably the greatest films primarily based on Jules Verne books (on this case, 1896’s “Dealing with the Flag” together with assorted others).

Initially launched within the U.S. in 1961 with an English dub and the title “The Fabulous World of Jules Verne,” this massively profitable and influential movie tells of the battle between a scientist (Lubor Tokoš) and an evil depend (Miroslav Holub) keen to construct a super-bomb. Being that Verne himself was an influential pioneer whose work straight influenced steampunk as an aesthetic, the alignment of his sensibilities with Zeman’s may solely yield one thing main, and certainly sufficient, “Invention for Destruction” visualizes Verne’s meticulous visions extra faithfully and dashingly than just about another movie adaptation in historical past.

The important thing to all of it is in Zeman’s incorporation of animation and painted-on results, with which he pushes each ingredient within the movie’s metal-plated mise-en-scène to extremes of plastic richness. Via this embrace of retrofuturistic Victorian maximalism, “Invention for Destruction” places on an unparalleled show of showmanship, whereas displaying an acute understanding of Victorian-era futurology — whereby industrial know-how might be each magic and menace.

7. Atlantis: The Misplaced Empire

There isn’t a different Disney flick fairly like “Atlantis: The Misplaced Empire,” a Michael J. Fox sci-fi film that deserves far more love. Expressly conceived by Gary Trousdale and Kirk Smart as a departure following the extra typical Renaissance pomp of “The Hunchback of Notre Dame,” this financially underwhelming however artistically bracing 2001 effort had the gumption to make use of Disney’s turn-of-the-century sources and artistic openness to do steampunk prefer it had by no means been completed earlier than.

Desperate to evoke the spirit of Jules Verne via the capabilities of big-budget animation whereas additionally paying homage to the oeuvre of comedian artist Mike Mignola (who additionally acts because the movie’s manufacturing designer), “Atlantis” brings to life an aesthetic that also feels startlingly futuristic 25 years later, regardless that the story being informed takes place within the 1910s. In actual fact, no different film may have made a extra acceptable record-breaker for many in depth use of CGI in a cel-animated Disney function; the movie’s whirring machines and majestic watercraft are all of the extra beautiful for being rendered in language-breaking 3D.

The plot, through which linguist Milo Thatch (Fox) and his expedition crewmates get caught between their reverence for Atlantis’ indigenous tradition and the capitalist voracity of their superiors, is comparatively easy. However that scarcely issues when “Atlantis” carries it out with such cinematic gusto on all fronts — and with such an irresistibly charismatic supporting forged in tow.

6. The Mysterious Citadel within the Carpathians

One other nice Czech adaptation of Jules Verne is 1981’s “The Mysterious Citadel within the Carpathians,” helmed by infamous comedy director Oldřich Lipský. Tailored from the 1892 novel “The Carpathian Citadel,” generally grouped as a minor work in Verne’s oeuvre but notable for having probably influenced Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” the movie retrofits the eerie Gothic tone of the supply materials into playful, eccentric, Terry Gilliam-esque comedy.

Extra narratively to-the-point than the novel, Lipský’s movie facilities Depend Teleke of Tölökö (Michal Dočolomanský), an opera singer reeling from the mysterious loss of life of his stage associate Salsa Verde (Evelyna Steimarová). Someday, whereas touring via the Carpathian mountains along with his servant (Augustín Kubáň), the depend meets forester Vilja Dézi (Jan Hartl), and the 2 males attain the fort of a harmful, obsessed baron (Miloš Kopecký) who could also be holding a still-living Salsa Verde captive.

The steampunk parts, largely equipped by legendary animator Jan Švankmajer because the movie’s prop designer, are within the fort. Retaining a mad scientist and inventor (Rudolf Hrušínský) as his minion, the baron has crammed his dwelling with ahead-of-its-time know-how, from televisions to elevators to automated sliding doorways. These parts, largely drawn from the novel, attest to Verne’s visionary genius, however simply as importantly, they make the fort of Baron Robert Gorc of Gorcena the type of unpredictable, vibrantly fascinating setting that matches foolish thriller comedies like a glove.

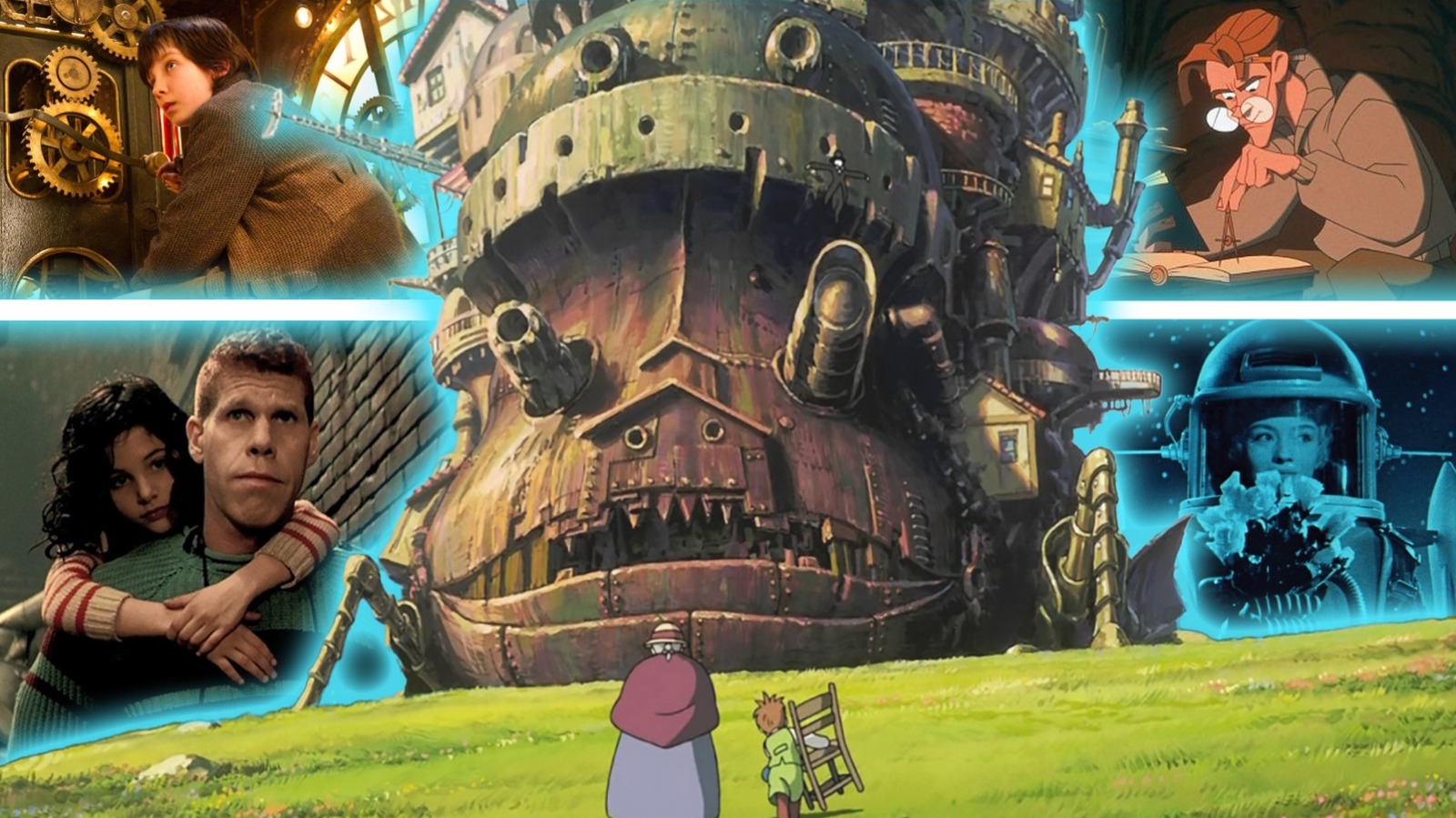

5. The Metropolis of Misplaced Youngsters

Within the Nineties, filmmakers Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet, each masters of the morbidly whimsical, teamed up for 2 singular movies that made a everlasting influence on the worldwide view of French cinema. The primary of these movies was 1991’s “Delicatessen,” which flirted with sci-fi however was extra of a darkish comedy. The second, 1995’s “The Metropolis of Misplaced Youngsters,” proved one thing any fan of Caro and Jeunet may already see coming: Their scenic design, with its predilection for dollhouse-like units and kooky compositions, paired completely with the giddy gaudiness of steampunk.

An authentic, underrated sci-fi film scripted by Caro and Jeunet together with Giles Adrien, “The Metropolis of Misplaced Youngsters” takes place within the type of fully-realized fairy story world that may carry a film by itself. Krank (Daniel Emilfork) is a scientist who’s getting older quickly because of his incapacity to dream — a predicament that compels him to kidnap youngsters and steal their desires for himself. Someday, he kidnaps Denrée (Joseph Lucien), the youthful brother of circus strongman One (Ron Perlman, talking French), and One units out to rescue him. Caro and Jeunet lay out the motion throughout dense, darkly-lit surroundings made up of tubes, contraptions, industrial dreamscapes, and ornate metalwork. It is a spellbinding, unrestrained cinematic imaginative and prescient delivered to bear with full lavishness — the sort that is changing into uncommon in films.

4. Adela Has Not Had Supper But

Generally often known as “Dinner for Adele” and “Adele Hasn’t Had Her Dinner But,” 1978’s “Adela Has Not Had Her Supper But” is one other mischievous steampunk triumph from Oldřich Lipský — however, as a substitute of taking a comical method to Jules Verne, the Czech auteur right here concocts a brilliantly witty send-up of the American dime novels centered round non-public eye Nick Carter.

Lipský and co-screenwriter Jiří Brdečka set the motion in late-Nineteenth-century Prague, the place Countess Thun (Květa Fialová) has simply introduced over Nick Carter (Michal Dočolomanský) from the U.S. and employed him to search out her lacking canine. Throughout his investigation, Carter comes throughout the extra attention-grabbing case of Baron Ruppert von Kratzmar (Miloš Kopecký), who retains feeding folks to his carnivorous plant Adela.

With Jan Švankmajer once more in tow (this time as animator), Lipský begins from the comparatively easy thought of parodying outdated pulp thrillers, and manages to develop that enterprise into the type of bold, deliriously artistic, mordantly witty, slyly profound bonkers comedy that could not be discovered anyplace else however in Czech cinema. Like in “Carpathians,” steampunk is among the essential elements, manifested each within the retro-technological lair of the botanist villain and within the more and more absurd devices of which Nick Carter avails himself.

3. The Status

Christopher Nolan’s “The Status” is an enthralling puzzle field of a film that retains getting higher because the brilliance of its building dawns on you. Tailored from the eponymous 1995 novel by Christopher Priest, it is essentially the most literal expression of certainly one of Nolan’s lifelong fascinations: The ability of the movie medium to work sheer magic earlier than the viewer’s eyes.

A fascination with magic additionally fuels the obsessive rivalry of Robert Angier (Hugh Jackman) and Alfred Borden (Christian Bale), Victorian-era London illusionists who preserve one-upping one another’s seemingly not possible methods. As their showbiz feud escalates to mutual sabotage and harmful rage, they discover themselves embroiled on the earth of science fiction: Angier turns into satisfied that Borden is creating tech-assisted methods with the assistance of Nikola Tesla (David Bowie, for whose casting Nolan had no plan B), and flies out to america to get in on the motion. However because the methods get realer, their stakes get larger.

Nolan displays arguably the best poise of his profession behind the digicam, painstakingly calibrating every scene, shot, and efficiency in order that the viewer will get correctly thrown for a loop by the movie’s mind-screwing twists. In actual fact, even the celebs weren’t informed how their methods had been completed. The combination of steampunk parts via Tesla’s begrudging participation is nothing in need of stupendous. Few different films so totally perceive the spine-tingling horror of science’s moral divestment below the logic of trade.

2. The Fabulous Baron Munchausen

There isn’t a different film like “The Fabulous Baron Munchausen.” Not even “Invention for Destruction,” nor another Karel Zeman movie, fairly compares to it. To see Zeman’s 1962 masterpiece a few Twentieth century astronaut (Rudolf Jelínek) who lands on the moon and finds it already occupied by Jules Verne characters is to be stunned at each flip, woke up to the belief that films can do that, and this, and that, and that — but by no means the wiser as to how.

Though nominally impressed by Verne’s “From the Earth to the Moon” and the literary tales of Baron Munchausen, the movie is thrillingly unbound on the extent of narrative, with an eagerness to leap weightlessly from thought to concept that behooves its nature as a youngsters’s story. On the extent of image-making, in the meantime, Zeman’s work in “Munchausen” has scarcely been matched by another filmmaker in historical past; he someway harkens again to the sense of openness and risk of early cinema, placing us within the thoughts of impressed fairgoers wandering right into a Méliès screening in 1903.

It is steampunk infused with the spirit of the period to which steampunk refers — sci-fi so temporally particular and wealthy in interval texture that it turns into timeless. If the style’s essence is retro science energized to the diploma of fantasy, it does not get purer than the meta-magic Zeman’s animated sequences.

1. Howl’s Shifting Citadel

Diana Wynne Jones’ 1986 novel “Howl’s Shifting Citadel” is an ebullient work of excessive fantasy that melds basic fairytale enterprise with themes of private autonomy, free will, and defiance of gender expectations. Incensed by the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, famous pacifist Hayao Miyazaki noticed in Jones’ novel the potential for a hard-hitting anti-war piece. To get that theme throughout, he blended her imaginative mythological building with early-Twentieth-century technological markers, grounded and dirty and grey, the higher to distinction guileless humanity with industrial devastation. The end result was the most effective steampunk film of all time.

Miyazaki’s most underrated masterpiece, “Howl’s Shifting Citadel” is a sometimes transcendent feat of cinematic creativeness, however nowhere else in Miyazaki’s oeuvre are the ethical underpinnings of his lush imagery any clearer. The titular fort alone is steampunk at its most interesting: a matryoshka of jaw-dropping sights, from its bulbous exterior to its endlessly shocking chambers and corridors, iconically forged towards dreamy pastures. However what actually seals it’s the anguished precision with which Miyazaki contrasts these pastures and the warfare equipment that rains hearth and loss of life on them. In Miyazaki’s fingers, steampunk is a conceptual extension of know-how itself, capable of be each enchanting and terrifying. In “Howl’s Shifting Citadel,” he makes use of the style to make materials the significance of rejecting warfare: The characters do, and, below the sway of the animation, so does the viewer.

Source link

#Steampunk #Films #Time #Ranked #SlashFilm